Authored by:

Authored by:

Rebecca Weaver Rinehart

Preaward Specialist

University of Northern Iowa

Email: rebecca.rinehart@uni.edu

This series of articles explores literary works that intersect with our professional interests in research, research administration, and university life.

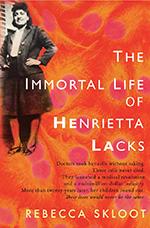

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is truly riveting and deserves the mass of praise it has received. Few works of nonfiction could be as difficult to put down as this book, which weaves together medical and personal history with issues of science, race and research ethics.

The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks is truly riveting and deserves the mass of praise it has received. Few works of nonfiction could be as difficult to put down as this book, which weaves together medical and personal history with issues of science, race and research ethics.

Before Henrietta Lacks died of cervical cancer in 1951, a sample of her tumor was given to Dr. George Gey, head of tissue culture research at Johns Hopkins. Dr. Gey had been trying for several decades to grow human cells in culture, and Henrietta’s were the first to succeed. Her cells grew with incredible vigor and never died, launching an industry and multiple medical revolutions. The HeLa cell line was used to develop the polio vaccine, cancer treatments, cloning and many other scientific and medical advances.

Henrietta’s family, meanwhile, was unaware of this for decades and never received any compensation. Lacking money, education, and health care, when researchers came seeking samples of their blood to further scientific understanding of HeLa cells, they believed they were being tested to see if they had the same cancer as Henrietta. Although the family was utterly failed by the researchers and others who benefitted from HeLa cells, the author does not tell a simplistic story. Dr. Gey in particular is presented sympathetically, as he never profited from his success either, and when he became ill with cancer, he offered himself up relentlessly as a research subject.

This series has so far focused on works of fiction, but this book is a fine example of literary nonfiction. As John McPhee argues in his recent book on the writing process, Draft No. 4, “A compelling structure in nonfiction can have an attracting effect analogous to a story line in fiction” (20). Rebecca Skloot masterfully crafted the structure and chronology of this book to create an experience of suspense for the reader. Scientific explanations, explorations of research ethics, the stories of Henrietta’s children, and the author’s experiences in researching the book all build on one another.

This is a book that everyone should read because of its importance, but researchers and research administrators are in a unique position to appreciate its ethical dimensions and dilemmas. The tension between the need for medical research to advance and the rights and privacy of individuals that is brought out so strongly in this story actually applies to all of us. The afterword delves into the ethics of contemporary research on human tissues. In 1999, it was estimated that at least 178 million Americans’ tissue samples were on file somewhere. Anyone who has ever been a patient literally has skin in this game. Under the Common Rule, medical researchers must now obtain informed consent from research subjects; however, consent is not required for studies on de-identified samples (Shuster).

The recent HBO film adaptation of this book is also worth watching. It stars Oprah Winfrey as Henrietta’s daughter Deborah, whose exploration of her mother’s history forms the emotional backbone of the book. The movie can’t substitute for reading the book, but it does movingly portray the abuses that Henrietta’s children suffered after her death, and the emotional repercussions of her cells’ immortality.

References

McPhee, John. Draft No. 4. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2017.

Barry K. Shuster, “In the Wake of Henrietta Lacks: Current U.S. Law and Policy on Control and Ownership of One’s Body Tissues Used in Medical Research,” The Journal of Healthcare Ethics & Administration 3, no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2017): 8-18, https://doi.org/10.22461/jhea.1.71614 .

Skloot, Rebecca. The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. Crown Publishers, 2010.

#insights