Volume LV, Number 2

Measuring Institutional Capacity for Grantsmanship: Constructing a Survey Tool for Institutions to Assess Institutional Support for Faculty and Administrators to Pursue Grant Funding

Lauren Gant, MA

Senior Professional Research Assistant

School of Education and Human Development

University of Colorado Denver

Christine Velez, MA

Associate Director

School of Education and Human Development

University of Colorado Denver

Mónica Torres, Ph.D.

Chancellor

NMSU Community Colleges

Abstract

Measuring the level of institutional capacity for grantsmanship within higher education informs administrators about the needs of their organization and where resources and institutional supports can be implemented to support faculty and staff. Receiving grant funding can lead to implementing cutting-edge programming and research support, which could improve the quality of education provided and, ultimately, student retention. While conducting an institutional capacity needs assessment is crucial for making data-informed decisions, there is a significant gap in institutional capacity research; specifically, there is no valid and reliable assessment tool designed to measure institutional capacity for grantsmanship. The present study aims to develop an assessment tool for higher education institutions to evaluate support systems and identify the needs of their faculty and administrators for grant writing efforts. The current study used a mixed-method approach over three phases to understand the indicators behind measuring institutional capacity for grantsmanship. We developed six reliable scales—promoting grant proposal writing, proposal writing (for faculty), proposal writing (for administrators), proposal writing (all respondents), submitting grant proposals, implementing grant activities, and managing awards. This study contributes to our understanding of institutional capacity and produced a reliable assessment tool to support grantsmanship.

Keywords: Institutional capacity, grant proposal writing, survey development, grantsmanship, needs assessment, equity

Introduction

Grant awards are a substantial source of income for higher education institutions that can fund cutting-edge programs and curricula, which enhance the institution's credibility and contribute to student retention (Stoop et al., 2023). Securing grant funding also supports research and evaluation endeavors that create opportunities for internal and external collaboration and partnerships and drive faculty career advancement (Krzyżek-Liburska, 2023). Given the significant potential for growth and innovation that accompanies acquiring grant funds, higher education institutions are increasingly interested in evaluating and expanding their organization’s capacity to support grantsmanship. However, grant awards are highly competitive, and faculty and administrators' experience and skill in grant writing and management can vary widely (Garton, 2012; Glowacki et al., 2020; Goff-Albritton et al., 2022; Porter, 2007). Applying for and managing grants is a multifaceted process that requires an understanding of different funding sources available, individual sponsor requirements, and how to create a compelling proposal, navigate the grant submission process, and maintain the award if the submission is accepted (Cunningham, 2020). Given the complexity of the grantsmanship process and the varying needs and interests among faculty and administrators to pursue funding, higher education institutions must implement institutional support systems to build capacity across their organizations (Krzyżek-Liburska, 2023).

Higher education institutions often place significant pressure on faculty and administrators to be the drivers of pursuing grantsmanship (Goff-Albritton et al., 2022; Scarpinato & Viviani, 2022). Universities and colleges often include applying for grant funding within faculty’s job descriptions and make eligibility for promotions and tenure predicated on successful grant acquisition (Goff-Albritton et al., 2022). However, while faculty and staff may be well-versed in their discipline's literature and research areas, this does not guarantee they have the skills and knowledge necessary to pursue grant opportunities (Glowacki et al., 2020; Porter, 2007). Faculty within a department represent differing career stages, levels of experience, and connections to networks of partners. Therefore, institutions need to provide support to accommodate these differences. Research has shown that faculty with access to institutional support and mentorship are more likely to acquire funding successfully (Krzyżek-Liburska, 2023). Comparatively, administrators are tasked with implementing effective structural supports to equip faculty with the knowledge and skills to pursue grantsmanship. Administrators must ensure their staff have the training, skills, and availability necessary to support faculty often while working with limited budgets (Scarpinato & Viviani, 2022). Therefore, institutions need to consider the responsibilities and needs of faculty and administrators to guide the types of institutional support implemented to ensure staff can confidently navigate the grantsmanship process.

In support of building capacity for grantsmanship, colleges and universities often offer institutional support such as grant writing workshops, institutional review boards, and dedicated offices or point persons who provide personalized assistance and communicate the resources available within the university (Krzyżek-Liburska, 2023). Grant writing workshops are frequently available to faculty and staff, providing crucial information and advice regarding the multifaceted grantsmanship process, which has proven effective in receiving a grant award (Glowacki et al., 2020). Internal review boards are another resource involving diverse experts within the organization who review and provide feedback on the design, sampling, and methodology of research and evaluation projects. Lastly, offices dedicated to supporting grant writing are implemented to provide personalized support through all stages of the grantsmanship process, including identifying funding opportunities available while considering eligibility criteria, mission alignment, deadlines, regulations, proposal development, budgeting advice, and management. Such institutional support and resources effectively provide higher education staff with knowledge and skills to enhance the staff's capacity to pursue grantsmanship. The importance of institutionalizing support systems within higher education cannot be overstated; however, institutions must also consider the unique needs of diverse faculty members when determining where institutional capacity could be established or expanded. Specifically, organizations should gather feedback on faculty perspectives to effectively support their individual faculty, thereby building capacity across the institution.

When considering which institutional supports need to be implemented or augmented to increase institutional capacity for grantsmanship, institutions should target which stages of grantsmanship that their faculty and staff identify as needing support. Institutional support is necessary at every stage of the grantsmanship process, including identifying funding opportunities, proposal writing, grant submission, grant implementation, and award management. Given that institutional support bolsters skills and knowledge in certain areas of the grantsmanship process, it is crucial to identify staff needs based on their varying experience and skill sets. Identifying funding opportunities can be daunting, especially among early-career faculty who may not know potential internal and external funding sources and their associated requirements and deadlines. Faculty must also understand how to manage those external partnerships (Memorandum of Understanding, subcontracting) and interact with grant offices and granting agencies (Krzyżek-Liburska, 2023). Therefore, identifying funding opportunities is influenced mainly by being attuned to networks of funders, which positions earlier-career faculty and faculty from smaller institutions at a disadvantage in obtaining grant funding successfully (Krzyżek-Liburska, 2023).

The other elements of successful grantsmanship are no easier for faculty members unfamiliar with the process. Proposal writing and submission is a multifaceted process that requires adequate institutional support. Grant writing varies greatly from the academic writing formatting and style, making it challenging for even esteemed faculty to know how to be competitive in obtaining grant awards (Garton, 2012; Glowacki et al., 2020; Goff-Albritton et al., 2022; Krzyżek-Liburska, 2023; Porter, 2007). The grant submission process is also tedious and complicated. It involves learning and navigating grant submission portals, interacting with an institutional review board, developing a project budget, and learning contractual and compliance procedures for accepting the award. Grant implementation and award management also involve complex processes: carrying out the grant activities, managing the budget, and managing contracts. Overall, the convoluting grantsmanship process requires institutional support at every stage to successfully build organizational capacity. Institutions need to consider the diverse needs of their institutions and measure the staff and faculty’s perceived effectiveness and weakness of current institutional support to make data-driven decisions about institutional needs.

Need for Instrument

While much of the existent literature regarding institutional support for research focuses on effective institutional strategies to build capacity for grantsmanship, there is a gap in empirical research addressing the extent to which faculty feel supported by their institutions to pursue and manage grant funding and can report their preferences for needed research support services (Goff-Albritton et al., 2022). Every institution and department has diverse faculty and staff at different career stages, with varying experience, interests, and needs; therefore, a needs assessment will allow an institution to make data-informed decisions to meet the unique needs of individuals, departments, and institutions instead of implementing uniform standards or programming. A survey instrument will allow institutions to evaluate support systems and identify the needs of their faculty and administrators who engage in grant-writing efforts to provide clearer pathways for obtaining resources (Honadle, 2018).

Understanding the degree to which faculty feel supported to pursue funding allows administrators the ability to make informed decisions and distribute necessary resources to build or improve effective support systems (Honadle, 2018). While some existing literature examines faculty’s perceptions of institutional support, the methods involve a qualitative approach through focus groups and interviews; however, there is a need to create a standardized, reliable approach to measure attitudes quantitatively. Qualitative data collection can be time-consuming and resource-heavy for institutions to replicate within their organization, especially if they want to collect longitudinal feedback. In addition, a validated instrument can ensure institutions are asking the right questions to capture the multifaceted steps needed to assess institutional capacity. Without understanding what it means to measure institutional capacity, institutions are left without clear guidance to implement institutional support. Further, even fewer studies include both faculty and administrators' perspectives on institutional support; therefore, a needs assessment mechanism is needed to gather administrator and faculty perspectives to understand the institutional capacity to support grantsmanship within an organization.

A standardized, open-access, free assessment tool also contributes to equity because it benefits all institutions that seek to understand how to build or improve support systems. The potential impact for smaller, underfunded universities and community colleges is amplified because these institutions may not have the capacity to thoroughly evaluate faculty and administrators’ perspectives on institutional support. Small departments and colleges need data to drive internal decision-making to ensure their limited budgets are allocated to areas identified by their faculty and administration. Specifically, Hispanic-serving institutions are historically underfunded and underrepresented in grant applications, so building a tool to bolster institutional support to build capacity creates more equitable opportunities to pursue grant opportunities. In grant applications and awards, diversity is crucial to supporting underrepresented institutions in implementing innovative programming, curriculum, and research. In service of equity, the current study seeks to provide a tool that all institutions can use to identify gaps and distribute the resources necessary to be competitive to acquire grant funding.

This multi-part study aims to construct a set of scales measuring institutional capacity for grantsmanship. The tool is intended to provide more equitable opportunities for institutions with a variety of staff knowledge and experience with grant writing, smaller institutions, and underrepresented institutions to build infrastructure to make them more competitive for grant funding. Creating a uniform and free survey instrument has the potential to equip institutions with the knowledge to make data-informed institutional-level decisions to drive building institutional capacity. The current study helps fill a gap in the literature regarding shared knowledge of the multifaceted approach to measuring institutional capacity while creating a practical tool to serve many institutions in pursuing grant funding opportunities.

Context

In the fall of 2018, New Mexico State University (NMSU) and California State University Northridge (CSUN) received funding through the National Science Foundation (NSF) to establish the first Hispanic Serving Institution (HSI) NSF HSI National STEM Resource Hub (the Hub). The Hub aims to support HSIs in building science, technology, engineering, and math (STEM) education capacity to increase STEM student retention and degree completion. Specifically, the Hub offers various services, workshops, and training to equip HSIs with the resources necessary to pursue NSF grant funding to support STEM education and pedagogy, especially among organizations with little or no experience applying for NSF funding. In pursuit of supporting the Hub’s mission, a team of external evaluators and representatives from NMSU and Doña Ana Community College (a branch campus of NMSU) collaborated to develop an institutional capacity for grantsmanship survey tool that would assess the extent to which faculty and administrators felt their organization provided grantsmanship resources and support.

Instrument Development

Developing the initial instrument for the present study was a collaborative effort between external evaluators and representatives from NMSU and Doña Ana Community College to effectively measure institutional capacity for grantsmanship. Additionally, this study's co-principal investigator (PI) is a member of the Hub leadership team and an experienced higher education administrator. The initial survey design drew on the PI’s years of experience attending grant workshops and conferences where higher education representatives discussed their lack of information concerning institutional capacity to support grantsmanship. Specifically, the Hub sponsored a series of free grantsmanship workshops for faculty, staff, and partners who were either affiliated with an HSI or wanted to collaborate with HSI partners, designed to bolster faculty skills in different areas of the grantsmanship process. Admission priority for the grantsmanship classes was granted to faculty within the first ten years of their academic tenure-track appointment and faculty representing diverse geographical locations and institutions. The grantsmanship workshops covered various topics, including examining the different stages of grantsmanship and the critical infrastructure needed to support and receive grants. The workshops were also structured to facilitate meaningful collaboration and networking opportunities during the sessions. Therefore, the HSI grant workshops created rich opportunities for higher education representatives from diverse backgrounds to share their experiences with the grantsmanship process, effective institutional supports, and the need for a more quantitative approach to examine the needs of faculty and administrators.

Attending the Hub grantsmanship workshop sessions allowed the PI to listen to the needs of faculty and administrators working in higher education. These discussions provided preliminary construct validity for the dimensions of grantsmanship used in the design for an initial survey. An evaluation team was then consulted to assist in refining the survey instrument. Evaluators recommended retaining 41 survey items and organizing the survey to include five constructs: 1) identifying funding opportunities, 2) proposal writing, 3) submitting grant proposals, 4) implementing grant activities, and 5) managing awards.

While there were five total constructs in the survey, proposal writing was subdivided into three scales: proposal writing (faculty only), proposal writing (administrators only), and proposal writing (all respondents). The proposal writing scales were designed to gather and analyze insights from both administrators and faculty separately on institutional capacity. Given their differing roles around grantsmanship, the Hub PI author decided to include administrators and faculty. Administrators were thought to have insights into what is needed to quickly obtain resources to strengthen institutional resources, while faculty are more involved in implementing programming. Collecting their responses separately was intended to provide a comprehensive picture of institutional capacity and encourage discourse regarding the needs of their organization.

An initial set of 41 survey items was developed to explore the identified dimensions of institutional capacity for grantsmanship. Items were written in the forward direction (a high score represents high institutional capacity). Respondents were asked to record their answers on a 4-point Likert scale; the wording for the anchor scale points varied to suit the item). Following the construction of the initial survey instrument, a three-part study using a multi-method approach was used to test its utility.

Methods

The present study aimed to develop a set of valid and reliable scales to measure institutional capacity for grantsmanship using a mixed-method approach over three phases. The first phase consisted of an item reliability analysis on pilot survey responses related to the different dimensions of institutional capacity for grantsmanship from a small sample. The second phase was designed to increase the instrument's validity by conducting interviews with survey participants to help refine the scales. The third phase involved administering the survey to a new and larger sample and using the results to explore the scales’ dimensionality and reliability. Overall, the study used triangulation by incorporating qualitative and quantitative methods across multiple data sources to confirm the accuracy of the findings in the study's final phase. Therefore, the current study used a thorough process to ensure the development of a comprehensive needs assessment tool.

Phase 1

A pilot study was conducted in January 2022 using the first draft of the survey, which included 41 items based on the five constructs.

Sample

The survey was sent to a small convenience sample of Hub members representing diverse institutions. The sample included Hub members from 14 different HSI institutions from seven states and Puerto Rico. The sample sites were chosen because they represented a diverse range of funding sources (public or private), institutional types (community college, 4+ year college, or research university), institutional sizes based on student enrollment (small = less than 5,000, medium = 5-15,000, large = over 15,000), and geographic locations. A total of 90 representatives from these institutions were invited to complete the survey.

A Qualtrics survey was administered online and remained open for 21 days. Survey reminders were sent 5 and 13 days after the initial survey launch. Survey respondents were informed that their participation was voluntary, that their responses were confidential, and that responses were being used to test the reliability of the scales within the survey. Participants were not provided with incentives to participate in the survey. The invitation to complete the survey was written by the Hub investigator author with their signature and email address to increase the likelihood of participation.

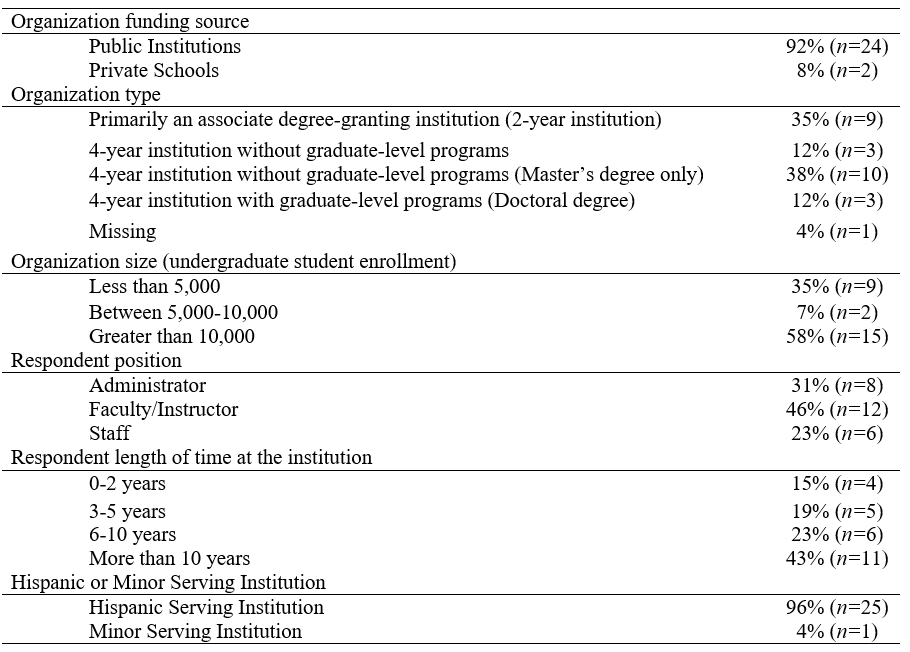

Table 1 shows the characteristics of individual respondents and their organizations. The 26 respondents included 18 faculty/staff (69%) and eight administrators (31%). Overall, most respondents represented public institutions (92%) that were considered Hispanic (96%) or Minority Serving (4%). Approximately a third of organizations represented (35%) were community colleges/associate degree-granting institutions. Many respondents (43%) had been at their institutions for over ten years..

Table 1

Phase 1 Sample Characteristics (n=26)

Process

An analysis was conducted to test the internal consistency reliability (Cronbach’s α) for the initial 41 items within each of the seven scales. Given the small sample size (n=26), this was considered an exploratory analysis; however, the results provided insights into areas of improvement before launching the survey to a larger sample.

Findings

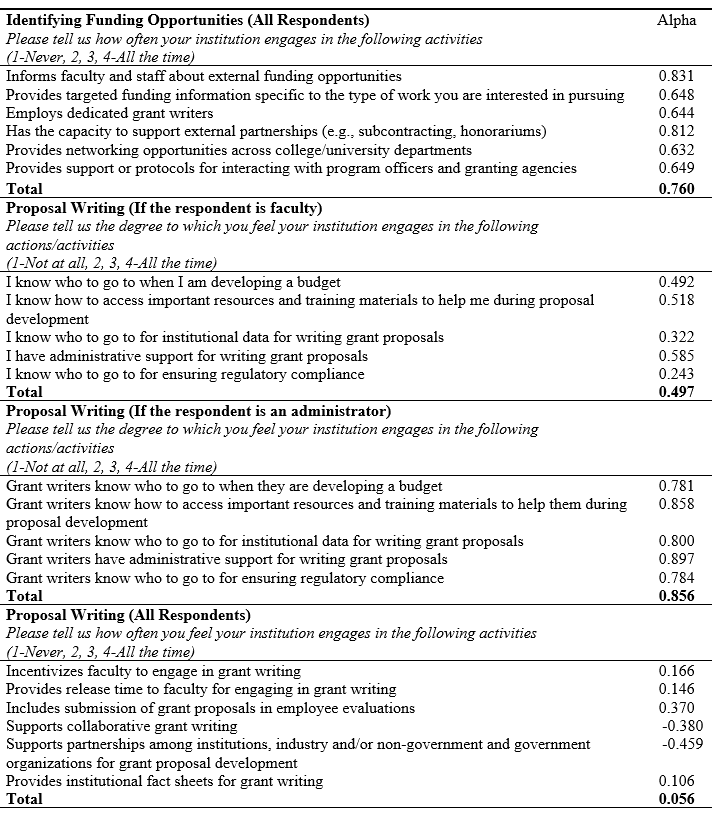

Table 2 shows the reliability scores for each item and the scale’s overall score.

Table 2

Item Reliability Analysis for Initial Measures (n=26)

Christine Velez, MA

Associate Director

School of Education and Human Development

University of Colorado Denver

1391 Speer Blvd., Suite 340,

Denver CO 80204

Mónica Torres, Ph.D.

Chancellor

NMSU Community Colleges

Las Cruces, New Mexico 88003

*Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Lauren Gant, MA, Senior Professional Research Assistant, School of Education and Human Development, University of Colorado Denver, 1391 Speer Blvd., Suite 340, Denver CO 80204, lauren.gant@ucdenver.edu.

Author Bios

Lauren Gant, M.A. received her master’s degree in applied Sociology at the University of Northern Colorado. Her research interests include organizational and institutional sociology.

Christine Velez, M.A., is the Associate Director of The Evaluation Center, University of Colorado Denver.

Mónica Torres, Ph.D., is the Chancellor of the NMSU System Community Colleges.

References

Aiken, L. R., & Groth-Marnat, G. (2009). Psychological testing and assessment. Pearson.

Creswell, J. W., & Creswell, J. D. (2022). Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (6th ed.). Sage.

Cunningham, K. (2020). Beyond boundaries: Developing grant writing skills across higher education institutions. Journal of Research Administration, 51(2), 41-57. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1293015

Garton, L. S. (2012, June 10-13). Grantsmanship and the proposal development process: Lessons learned from several years of programs for junior faculty. Paper presented at 2012 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition, San Antonio, Texas. https://doi.org/10.18260/1-2--21439

Glowacki, S., Nims, J. K., & Liggit, P. (2020). Determining the impact of grant writing workshops on faculty learning. Journal of Research Administration, 51(2), 58-77. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1293016

Goff-Albritton, R. A., Cola, P. A., Walker, J., Pierre, J., Yerra, S. D., & Garcia, I. (2022). Faculty views on the barriers and facilitators to grant activities in the USA: A systematic literature review. Journal of Research Administration, 53(2), 14–39. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1362093

Honadle, B. W. (1981). A capacity-building framework: A search for concept and purpose. Public Administration Review, 41(5), 575. https://doi.org/10.2307/976270

Krzyżek-Liburska, S. (2023). Support systems for research proposals–Institutional approach. In J. Nesterak & B. Ziębicki (Eds.), Knowledge, economy, society: Increasing business performance in the digital era (pp. 173-181). Institute of Economics, Polish Academy of Sciences.

Porter, R. (2007). Why academics have a hard time writing good grant proposals. Journal of Research Administration, 38(2), 37-43. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ902223

Scarpinato, K., & Viviani, J. (2022). Is it time to rethink how we support research: Teams, squads and mission? – An opinion. Journal of Research Administration, 54(1), 87–93. https://www.srainternational.org/blogs/srai-jra2/2023/03/14/is-it-time-to-rethink-how-we-support-research-team

Stoop, C., Belou, R., & Smith, J. L. (2023). Facilitating the success of women’s early career grants: A local solution to a national problem. Innovative Higher Education, 48(5), 907–924. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10755-023-09661-w